FLSHGH

Scruple Co. /

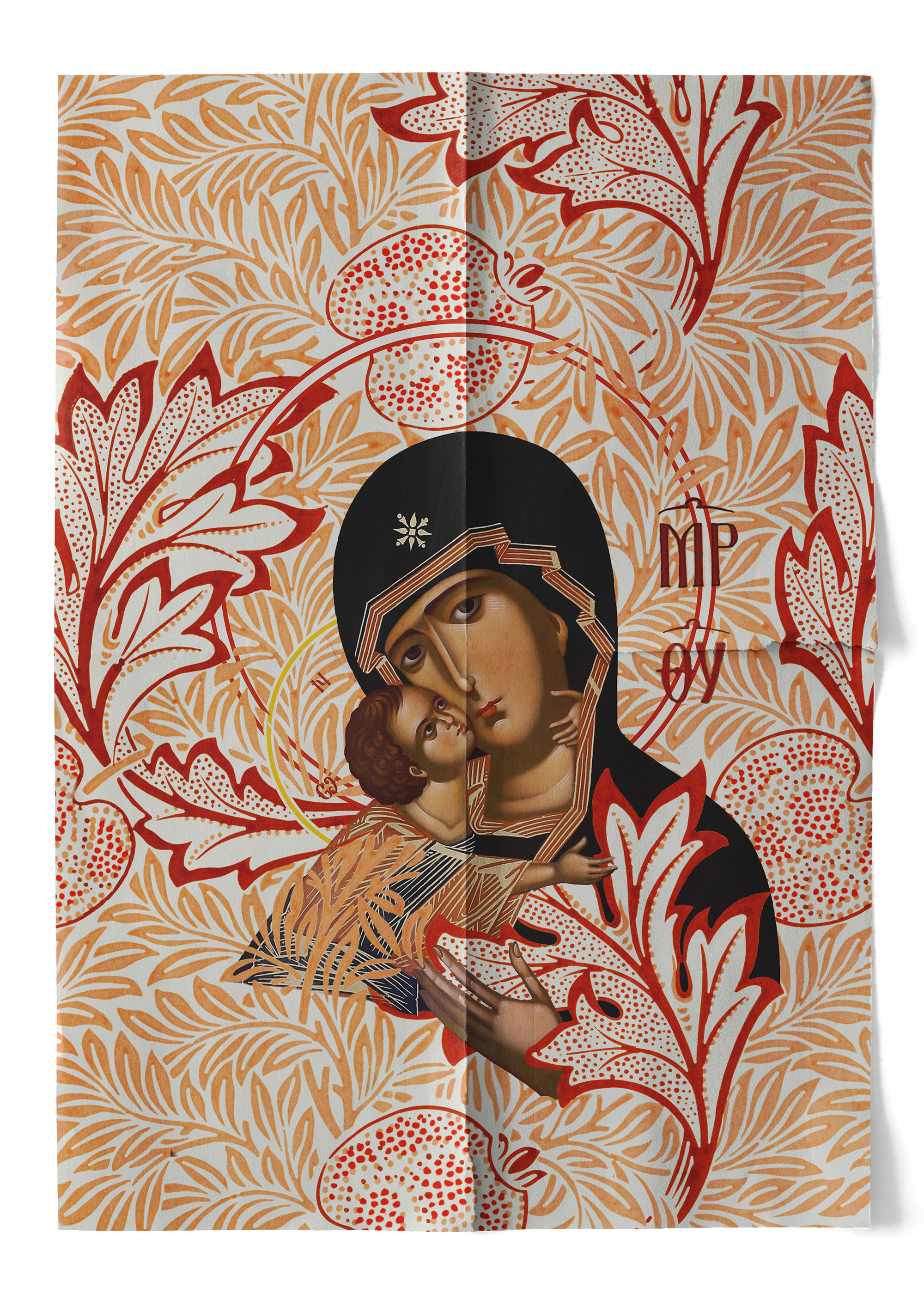

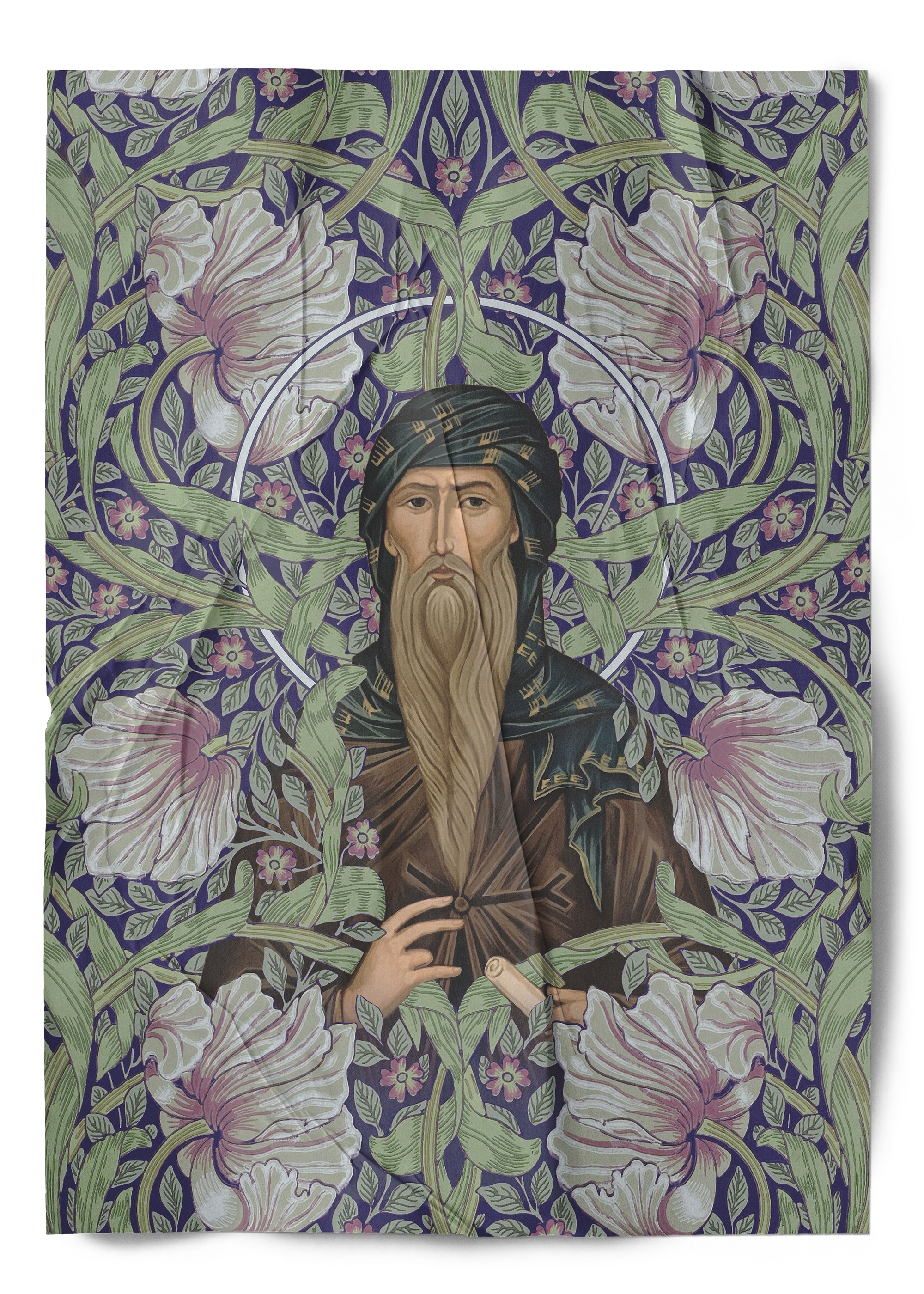

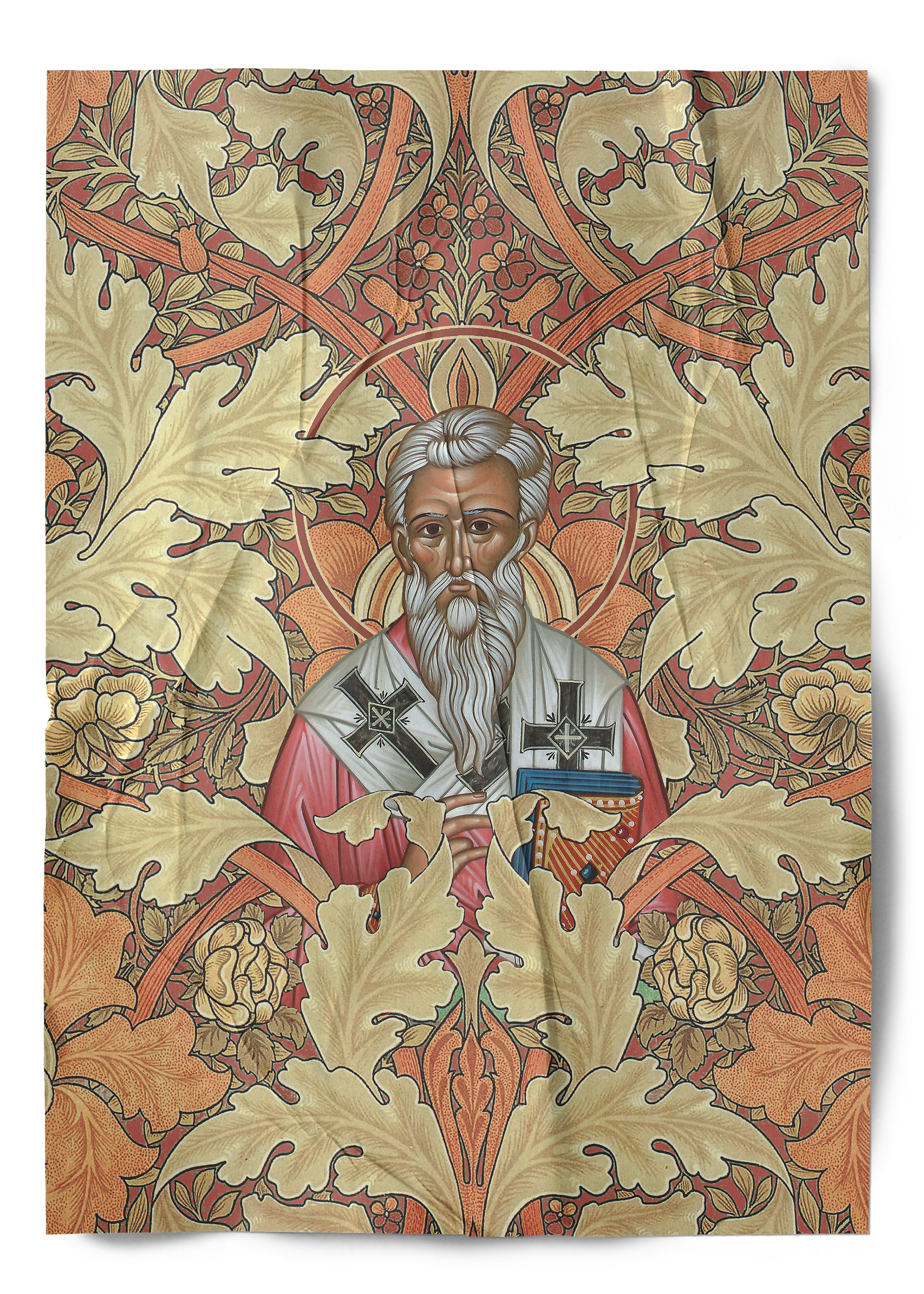

William Morris x Orthodox Icons

Research & Inspiration

“William Morris, [was] part of a broad reform movement responding to industrialism and the decline of true craftsmanship and artistic integrity in Western society”

William Morris: The Man Who (Re)Discovered Art with a Little "a"

by David Bruce Hegeman

William Morris & The Historical Context

William Morris was a raised as a Christian during the height of the Victorian era in the United Kingdom, where the arts and religion exercised themselves in kindred spirit through atraditional freedom. The Enlightenment era had brought on a neo-Christian intellect that flourished during his time.

Historically, Christian Protestantism (with all of its facets) was at its peak in terms of a crisis of faith and liberty from strict orthodox dogmas. Similarly, the artistic movements of the era were characterized by opposition of religious and classical norms. “Conservative” philosophies of God-centered morality were being shunned in favor of popular nouveau scientific based reason and logic. This in turn motivated and accelerated the worldly emotional and imagintive spontaneous individuation in the mind of man. This evolving and nonconforming humanist psyche continually affected the Christian church—especially the authority—which was more divided than ever over such ecclessial intransigence.

Fueled by the evolving theocracy, innovative machinery breakthroughs, and thriving commercialism, the Industrial Revolution inevitably devolved man into a cog within the growing consumer machine.

Historically, Christian Protestantism (with all of its facets) was at its peak in terms of a crisis of faith and liberty from strict orthodox dogmas. Similarly, the artistic movements of the era were characterized by opposition of religious and classical norms. “Conservative” philosophies of God-centered morality were being shunned in favor of popular nouveau scientific based reason and logic. This in turn motivated and accelerated the worldly emotional and imagintive spontaneous individuation in the mind of man. This evolving and nonconforming humanist psyche continually affected the Christian church—especially the authority—which was more divided than ever over such ecclessial intransigence.

Fueled by the evolving theocracy, innovative machinery breakthroughs, and thriving commercialism, the Industrial Revolution inevitably devolved man into a cog within the growing consumer machine.

Empirical idealogy flourished in tandem, as the quest into the depths of the meaning of life amidst widespread nihilism created atheistic polar worlds of nominalism and solipsism. Philosophy was looking outside of rules of the Church and instead into a realm based on unscrupulous self-expression. This trend exposed the danger of a mode of being without a galvanized metaphysical theology or philosophy to cure the pangs of an increasingly technological and liberated society. And so, a world without God as supreme arbiter

inevitably added to man’s sense of existensial dread and ultimately a sense of meaninglessness, as humanity found itself deeper in “sinful lusts” that lead to uninterrupted abuse. In the face of science’s ability to solve many of the world’s problems, it failed to adequately address man’s sense of placement in the cosmos. Post-Enlightenment Western spirituality was exemplifying and pivoting the popularized world in a new direction based on a relative materialism—devoid of a divine being—where man and nature exist alone as the source of knowledge.

Although the onset of a growing culture based on secular daydreaming was rampant, Morris was driven to pursue the trade through the medieval workshop ethos. Ironically, this craft was traditionally centered around Christian monastic mediums—in another perfect moment of historical duality.

Although the onset of a growing culture based on secular daydreaming was rampant, Morris was driven to pursue the trade through the medieval workshop ethos. Ironically, this craft was traditionally centered around Christian monastic mediums—in another perfect moment of historical duality.

William Morris responded to the increasing angst of the artist in the industrialized world by delivering the craftsman to his natural handmade state through art as a form of functional, yet beautiful commodity—affordable to the masses and not just the elites.

Morris is known as the pioneer of the British Arts and Craft movement, who answered the call of the vanishing intrinsic mode within the artist.

To Morris’ credit, despite his lack of confidence in the historically widespread professed truths of Christianity, as a hero cynic of The Gospels, he participated in a Western art revival that any fairly judgemental Christian would applaud. His work is undeniably orantely divine.

To Morris’ credit, despite his lack of confidence in the historically widespread professed truths of Christianity, as a hero cynic of The Gospels, he participated in a Western art revival that any fairly judgemental Christian would applaud. His work is undeniably orantely divine.

...

“The remark indicates a relationship that several of Morris’ early stories and poems have to each other. In Lindenborg Pool, the protagonist seeks, but does not receive, a sign from God. In The Hollow Land, two medieval knights who thought they did have signs from God finally realize that they have only taken their own judgments for His. And even The Judgment of God, in spite of its title, argues that men should not attempt to ascertain God's judgment.”

“William Morris and the Judgment of God.” by John Hollow

PMLA 86, no. 3 (1971): 446–51. https://doi.org/10.2307/461109.

PMLA 86, no. 3 (1971): 446–51. https://doi.org/10.2307/461109.

Orthodox Icons

Orthodox icons have a rich history, also one that would take a novel to ultimately define accurately, especially through an eclessial historical lens. The artworks have a deep reverance as symbols of the saints they depict and a set of certain rules applies when creating them in order to remain within boundaries of Orthodox tradition. Having once been banned by emperor Leo III during the 8th century Byzantine empire, the icons were to all be destroyed as a crime against the Church, committing idolatry. The artists are often left anonymous and are commonly created by priests, presbyters, monks or nuns within the local church or monasteries of where they reside. Equally humble and lavish projections of the Holy Spirit through man and woman, no doubt.

“The Icon is never complete in itself. It can never stand alone as an autonomous work of art, but refers to a spiritual dimension and forms part of a concrete, religious practice. As it expresses itself through a holy symbolic language, it cannot be read without a knowledge of Orthodox theology and spirituality”

The Mystical Language of Icons

by Solrunn Nes

“The theological justification of the icon was derived by the Seventh Ecumenical Council from the fact of the Incarnation of God. God became human for the elation and deification of Man. This deification becomes visible in the saints. The Byzantine theologian often sets the calling of an icon painter on an equal level with that of a priest. Devoted to the service of a more sublime reality, he exercises his objective duty the same way as the liturgical priest. The "spiritual genuineness" of the icon, the cryptic, almost sacral power to convince, is not alone due to accurate observation of the iconographic canon, but also the ascetic fervor of the painter.“

The Meaning of Icons,

by Leonid Ouspensky, Vladimir Lossky (1999)

by Leonid Ouspensky, Vladimir Lossky (1999)

END OF RESEARCH

“Beauty is nothing other than the promise of happiness.”

Stendhal

De L'Amour (On Love) (1822), Ch. 17, footnote